On Historical and International Legal Accountability of Finland for the Occupation of Karelia During Great Patriotic War (WWII) (1941–1944) (Report by the Representative office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation in Petrozavodsk)

Representative office

of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation

in Petrozavodsk

Report:

“On Historical and International Legal Accountability of Finland for the Occupation of Karelia During Great Patriotic War (WWII) (1941–1944)”.

Petrozavodsk

2025

GENERAL INFORMATION

September 30, 2024, marked 80 years since the liberation of Karelia from Nazi and Finnish occupation forces. Given the need to reaffirm the historical truth, it is again relevant to direct the attention of the world community to the crimes committed by Finland during its occupation of Karelia from 1941 to 1944. While these atrocities were adjudicated by a Finnish court under the agreement between the USSR and Finland, the proceedings demonstrated excessive leniency towards the accused.

On August 1, 2024, the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia ruled on the application of the Prosecutor of the Republic of Karelia to establish a fact of legal significance. The Court recognized crimes committed by Nazi occupation forces and Finnish occupation authorities and troops on the territory of the Karelo-Finnish SSR during the Great Patriotic War (WWII) (1941-1944) as war crimes and crimes against humanity. These crimes, defined in the Charter of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal (August 8, 1945) and affirmed by UN General Assembly Resolutions 3(I) (February 13, 1946) and 95 (I) (December 11, 1946), were perpetrated against at least 86,000 Soviet citizens. The victims comprised civilians and prisoners of war serving in the Red Army (the armed forces of the USSR). Furthermore, the Court recognized these acts as genocide against national, ethnic, and racial groups representing the population of the USSR - the peoples of the Soviet Union. This genocide formed part of a plan by Nazi Germany and its ally, Finland, to expel and exterminate the entire local population of the occupied Soviet territories to colonize the land.

The evidence presented to the court confirmed that the occupiers systematically tortured civilians and prisoners of war. This included subjecting them to forced labor under brutal conditions, physical beatings, the prolonged denial of medical care, and confinement in inhumane concentration camp conditions. Collective punishment was routinely applied to civilians and prisoners of war for even minor acts of disobedience. Based on evidence presented during hearings, the court established that over 26,000 civilians and prisoners of war perished during the occupation. These deaths resulted from execution, torture, starvation, and disease. Furthermore, the occupiers deliberately destroyed cities, villages, and industrial and agricultural infrastructure. The total economic and infrastructural damage inflicted upon the region, adjusted for inflation to current ruble values, exceeds 20 trillion rubles[1].

Considering the ruling of the Supreme Court, this report provides a legal assessment of Finland's conduct during World War II. The documented violations include violations of international treaties, crimes against peace, the implementation of a brutal policy in the occupied territories, which entailed war crimes and crimes against humanity, including genocide, ethnic segregation, cruel treatment of non-Finno-Ugric population and prisoners of war.

The evidentiary record concerning the Finnish occupation regime is extensive and meticulously details unlawful acts. While comprehensive examination exceeds scope of the report, the established pattern confirms large-scale war crimes comparable in severity to those perpetrated by Nazi Germany. The evidence leaves no reasonable doubt that these violations stemmed principally from the Nazi-inspired concept of a “Greater Finland”.

Finnish leadership deliberately disregarded international rules, regulations, and agreements in conducting their brutal occupation policy against Soviet civilians in Karelia. The Finnish Military Administration of Eastern Karelia[2], under direction from national leadership, systematically planned the temporal and geographic execution of war crimes to advance strategic objectives. Documentation confirms most atrocities resulted from calculated premeditation rather than incidental conduct.

During World War II, Finland allied with Nazi Germany and violated its international obligations by waging a war of conquest against the USSR.

In 1941, Finnish forces launched an offensive, seizing control of nearly the entire Karelian Isthmus and most of Soviet Karelia - including Petrozavodsk - while advancing to northern approaches of Leningrad and participating in its blockade.

Modern Russian and Finnish historiography have substantially documented the Finnish occupation regime and its associated crimes. Declassified archives further reveal that occupation policy of Finland in Karelia (1941–1944) centered on establishing an ethnically purified “Greater Finland”, incorporating Soviet Karelia. Under this policy Finno-Ugric peoples (Karelians, Vepsians, Ingrians, Finns) were designated for Finnish citizenship and the Russian population was systematically isolated through internment in concentration camps, labor camps, and prisons, with planned expulsion from the territory.

In 2020, a regional volume of the collection on Nazi crimes against the Soviet civilian population, “Without Limitation Period”, was published[3] edited by S.G.Verigin, A.N.Lesonen, K.A.Morozov, E.V.Usacheva and Y.M.Kilin, which examined in detail the problems of the situation of the Russian population in Karelia during the Finnish occupation in 1941–1944.

The scholarly introduction to this collection was authored by Ph.D. in history S.G.Verigin, a longtime researcher of this subject. His contribution surveys relevant literature on the Finnish occupation regime organization and provides a comprehensive overview of its wartime crimes.

The collection draws extensively on declassified archival documents from the National Archives of the Republic of Karelia and the FSB Directorate for the Republic of Karelia, materials that became accessible in 2020. These include interrogation protocols from civilian concentration camps and PoW-labor camps, prisoner-of-war interrogation records, investigative files from the 4th Department of the NKVD of the Karelo-Finnish SSR, witness testimonies documenting crimes in occupied Karelia, and other critical sources. Particularly significant is a 1958 KGB USSR list identifying 54 individuals implicated in mass murders, including administrators of Finnish-operated camps in Karelia.

The collection integrates Russian and Finnish scholarship: K.A.Morozov's “Karelia during the Great Patriotic War”[4]; V.Merikoski’s “Finnish Military Leadership in Eastern Karelia in 1941-1944”[5]; O.V.Kuusinen's “Finland without a Mask”[6]; A.Laine's “Two Faces of Great Finland: The Situation of the Civilian Population of Eastern Karelia” and “The Civilian Population of Eastern Karelia under Finnish Occupation in World War II”[7]; H.Seppälä's “Defense Policy and Strategy of Independent Finland”[8], “Finland as an Aggressor”[9], and “Finland as an Occupier”[10]; and J.Kulomaa's “Jaanislinna: The Finnish Occupation of Petrozavodsk, 1941-1944”[11]. It further incorporates published document collections such as “On Both Sides of the Karelian Front”[12] and “Unknown Karelia: Documents of Special Agencies on the Life of the Republic, 1941-1956”[13], alongside postwar publications by the State Extraordinary Commission on Finnish occupation crimes Fascist Invaders in the Temporarily Occupied Territory of Karelia in 1941-1944 were published in the USSR.[14]

Primary testimonies are represented through memoirs including “Fate”[15] and “Captive Childhood (recollections of former child prisoners)”[16], V.S.Lukyanov's “Tragic Zaonezhye”, N.I.Deniskevich's “In a Finnish Concentration Camp”, and the 2023 collection “We Are Still Alive! The Fates of Former Underage Prisoners”.[17] The latter was compiled by K.A.Nyuppieva, who herself survived internment and long chaired the Karelian Union of Underage Prisoners of Nazi Concentration Camps.

Dr. Verigin's analysis concludes that archival evidence “demonstrates catastrophic mortality rates among Russian and other non-Finno-Ugric populations in the camps, resulting from deliberate starvation, forced labor, and disease”. Documents explicitly identify perpetrators and corroborate systematic torture of prisoners - including women, elderly, and children - by camp personnel who viewed them as subhuman.

These findings are substantiated by the 2024 publication of the Russian Military Historical Society “The Black Book: A Brief History of Swedish and Finnish Russophobia”[18].

Since 2020, Russia's Investigative Committee has pursued a criminal genocide case (under Article 357 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) based on the declassified documents, testimony from survivor organization including the Union of Former Underage Prisoners, and other evidence. Investigators aim to establish individual accountability for crimes against Soviet citizens.

This report synthesizes these judicially recognized facts from the Supreme Court of Karelia, witness accounts, archival materials, and scholarly research to provide a comprehensive legal-historical assessment.

CASE STUDIES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OFFENSES OF FINLAND

During World War II (1941–1944), Finland aligned as an ally of Nazi Germany. While the Nuremberg Tribunal did not adjudicate Finnish atrocities under the terms of the 1947 Finland-USSR Peace Treaty, these actions demonstrably satisfy the definitions of crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity established by the Charter of the Tribunal. These definitions derived from international treaties binding upon Finland at the time, including the 1907 Hague Conventions, the 1928 Treaty on the Renunciation of War, the 1929 Geneva Conventions, etc.

This legal classification subsequently underpinned key international instruments, notably the 1968 Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity.

Accordingly, this report will apply the generalized definitions articulated in the Nuremberg Principles (1950) – the principles of international law recognized by the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and affirmed in its judgment – as codified by the United Nations International Law Commission. The following classifications from the Nuremberg Principles provide the legal framework for this analysis:

(a) Crimes against peace: Including the planning, preparation, initiation, or waging of wars of aggression, wars violating international treaties/agreements, or participation in conspiracies to execute such wars.

(b) War crimes: Violations of the laws or customs of war, encompassing murder, cruel treatment, or deportation of occupied civilians; mistreatment of POWs or persons at sea; hostage executions; plunder of property; and unwarranted devastation of settlements unjustified by military necessity.

(c) Crimes against humanity: murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts against civilian populations, or systematic persecutions on political/racial/religious grounds – particularly when linked to crimes against peace or war crimes.

Notwithstanding this legal framework, Finnish wartime offenses were adjudicated domestically under the 1947 Finland-USSR Peace Treaty. Compared to the rigorous standards of the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals, Finnish courts demonstrated excessive leniency. Numerous individuals convicted for war crimes during the occupation of Soviet Karelia received symbolic, if not laughable, disproportionately lenient sentences, including minimal custodial terms (under one year, often reduced to months) or nominal fines.

1. CRIMES AGAINST PEACE

AGGRESSION AGAINST THE USSR

The Finnish leadership actively participated in waging aggressive war against the USSR. During summer 1940 negotiations in Helsinki and Berlin, Finnish and German officials negotiated concrete agreements for military cooperation. This alliance was formally articulated in Hitler's Directive No. 21 (Operation Barbarossa) dated December 18, 1940, which explicitly designated combat role of Finland [19]: “1. [...] we can count on the active participation of Romania and Finland. The High Command of the Wehrmacht will [...] establish in what form the armed forces of both countries will be subordinated to German operational command upon their entry into the war.

3. Finland must cover the deployment of the separate German North Finland Group (elements of the XXI Mountain Corps) advancing from Norway and conduct joint operations with them. Finland is further assigned responsibility for capturing the Hanko Peninsula”.

Meeting between Hitler, Marshal Mannerheim, and President Ryti in Imatra, 4 June 1942

The verdict of 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal explicitly confirmed alliance of Finland with Nazi Germany, stating: “Germany drew Hungary, Romania and Finland into the war against the USSR”. This collaborative relationship manifested operationally when Finland permitted German forces to stage attacks from its territory prior to the formal Soviet declaration of war on June 26, 1941. Finnish archival sources acknowledge that Helsinki committed to provide northern Finland as a base for German military operations and to launch its own offensive in Eastern Karelia.

Strategic objectives were further clarified at Hitler's July 16, 1941, conference, where participants documented Finnish territorial ambitions: “The Finns want Eastern Karelia.” This expansionist agenda materialized through direct military cooperation, including Finland's provision of airfields from which Luftwaffe aircraft conducted bombings against Soviet targets.

Swedish historian Henrik Arnstad characterizes Finland as “the only democracy that entered into an alliance with Hitler of its own volition”.[20]

No credible evidence indicates Soviet intentions to attack Finland prior to invasion of Germany. While Finnish historiography frames its military actions as a “Continuation War”, territorial acquisitions extended beyond regions lost under the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty. By initiating aggression, Finland violated binding international norms it had committed to uphold. Specifically, Finnish authorities planned and executed an aggressive war against the USSR “in violation of international treaties, agreements and assurances”, formally declaring war on June 26, 1941.

Helsinki violated the provisions of the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty. Article 3 stipulated: “Both Contracting Parties undertake to mutually refrain from any attack against each other and shall not conclude alliances or participate in coalitions directed against either Contracting Party”. By the time Soviet forces bombed Finnish airfields on June 25, 1941, it was evident that Helsinki had entered a coalition with Nazi Germany and permitted Germany to use Finnish territory to launch offensives from northern Finland into the USSR’s northern districts and conduct bombing raids against the Soviet Union. These actions occurred in June-July 1941 – contemporaneous with Berlin’s declaration of war against Moscow. Finland, with German support, intended to attack the USSR.

2. CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY AND WAR CRIMES

Following its aggressive expansion, Finnish authorities implemented a policy of ethnic reorganization based on the “Greater Finland” concept developed by the “Karelian Academic Society”. This plan envisioned territorial consolidation under Finnish control exclusively for ethnic Finns and related Finno-Ugric peoples. Concurrently, the Russian and other non-Finno-Ugric populations were subjected to systematic persecution through widespread cruel treatment, forced internment in concentration camps and preparation for mass deportation. Archival evidence confirms these actions were executed pursuant to explicit directives from the Finnish military and civilian leadership.

Pursuant to the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia's judicial findings, approximately 86,000 residents remained within the occupied territory of the Karelo-Finnish SSR during 1941–1944. Of these, 25,000 were subjected to internment in Finnish-administered concentration camps at various intervals. The judicially recognized minimum mortality figures document: 7,000 civilian deaths and 18,000 prisoner-of-war fatalities [21].

Evidence confirms that certain war crimes were premeditated prior to military operations. In Karelia, systematic economic exploitation of occupied territories and persecution of non-Finno-Ugric civilians were meticulously planned before hostilities commenced. Similarly, documented state planning incorporated the large-scale deployment of occupied populations for coerced labor, explicitly integrating this measure into wartime economic framework of Finland.

Civilian populations endured systematic hardships: deliberate starvation and forced labor in forestry and construction sectors. Concurrently, Finnish authorities implemented coordinated confiscation of both public and private assets, transferring resources from occupied territories to strengthen national economy of Finland.

ATROCITIES AGAINST CIVILIAN POPULATION: KILLINGS AND INHUMANE TREATMENT

The Finnish occupation regime in Soviet Karelia, driven by an ideology aiming for an ethnically homogeneous “Greater Finland”, committed numerous crimes against civilians. Implementing a policy of ethnic segregation, the military administration categorized the population into two groups: privileged individuals of Finno-Ugric descent and unprivileged Slavs. While Finno-Ugric peoples were slated for potential citizenship, social benefits, and freedom of movement in annexed territories, the Slavic population, including women and children, was subjected to internment in concentration camps (euphemistically termed “resettlement camps”), exploitation, deliberate deprivation, and plans for deportation. Official policy mandated significantly lower food rations and wages for the unprivileged Slavic group, typically 50-60% below those allocated to the privileged group. This systematic discrimination, resulting in harsh living conditions, was a direct consequence of directives issued by the Finnish leadership.

Preceding the military campaign, the Finnish command formulated a plan in mid-June 1941 titled “Plans for some measures in Eastern Karelia”, reflecting ambitions like the German “Generalplan Ost”. This plan asserted historical Finnish claims to Eastern Karelia. These expansionist aims were further underscored in a study commissioned by President Risto Ryti, published in autumn 1941 as “Living Space of Finland”. The aggressive intentions of the Finnish leadership during this period are documented in official state documents and the orders of Commander-in-Chief Carl Gustaf Mannerheim.[22]

Historical evidence indicates that Finland established concentration camps for civilians prior to Nazi Germany. This policy was formalized in Order No. 132 issued by Commander-in-Chief Carl Gustaf Mannerheim on July 8, 1941, which explicitly directed: “Russian population shall be detained and placed in concentration camps”. The first of fourteen primary concentration camps was established in Petrozavodsk on October 24, 1941. This detention network rapidly expanded across the occupied territory. In addition to these civilian concentration camps, the Finnish occupation authorities created an extensive system of forced detention facilities, including: 34 labor camps and penal labor battalions, 42 camps and companies for Soviet prisoners of war, 9 prisons, and 1 colony. The concentration and labor camps operated numerous sub-camps and branches, creating a pervasive system of forced detention that reached into nearly all populated areas under Finnish control.

One of the Concentration Camps in Petrozavodsk, 1941–1944. National Archives of the Republic of Karelia

The documented evidence indicates a high mortality rate within the Finnish concentration camps. This resulted directly from the systematic deprivation inherent in the detention conditions: severe malnutrition (inadequate and nutritionally deficient food rations); extreme overcrowding: Men, women, and children of all ages were confined together in unheated barracks, with a standard allocation of only 1 to 3 square meters per person; lack of medical care: absence of essential healthcare services; forced labor: harsh working conditions compounded physical deterioration, physical abuse: prisoners faced beatings and humiliation for minor infractions. Reported instances exist of individuals, including children, being executed for attempting to leave the camp perimeter in search of food.

The official daily ration for camp inmates was: 300 grams of flour, 15 grams of sugar, and 50-100 grams of horse meat or sausage per week. These rations were consistently insufficient, often failing to be distributed in full due to systemic discrimination and corruption. Calculated nutritional analysis demonstrates this ration provided less than half the calories required for basic health maintenance, resulting in average weight loss of 3 to 7 kilograms per month. Such deliberate, chronic caloric deficit inevitably led to severe weakening the body and directly contributing to the high death toll.

Epidemics of dysentery, typhus, pediculosis and other infectious diseases raged in the camps. Medical care was not provided properly; necessary medications were lacking. The best cure for all ailments, a means of sanitation, was to place people, including children and the elderly, in rooms where the temperature was above 100 degrees Celsius. The mortality rate in some camps reached 20 people per week.

Victims of Fascism, Petrozavodsk.

Photo by Galina Sanko/TASS, 1944

Prisoners from the age of 14 were forced into slave labor. The death rate from exhaustion in concentration camps exceeded the Nazi German figures (13.75% versus 10%). There is still no precise data on the number of deaths. The Finnish military administration compiled lists of the dead extremely carelessly, and the records of those punished, according to witnesses, were destroyed by the occupiers before retreating.

This documented pattern of systematic deprivation and its fatal consequences was corroborated under oath during proceedings before the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia. Testimony was provided by individuals who had been imprisoned as juveniles, including L.P. Makeeva (Camp No. 5, Petrozavodsk), T.V.Kardash (Camp No. 3, Petrozavodsk), G.M.Chapurina (Camp No. 2, Petrozavodsk), K.A.Nyuppieva (Camp No. 6, Petrozavodsk), L.P.Lukyanenko (Camp No. 7, Petrozavodsk), V.N.Kharkin (Camp No. 5, Petrozavodsk), Y.I.Fesheva (Camp No. 5, Petrozavodsk), S.P. Mikhailova (Camp, village of Kolvasozero).

Witness testimony consistently identifies extreme, debilitating hunger as the defining horror of the Finnish concentration camps. Survivors described wholly inadequate rations, typically consisting of flour, spoiled sausage, hardtack biscuits, and thin gruel made from turnips or potato peelings. This systematic starvation led directly to deaths among all age groups, including young children and the elderly. Malnutrition was endemic, with nearly all prisoners suffering from scurvy and related deficiency diseases. Desperate attempts to find food carried lethal risks: children and adolescents would forage for berries, mushrooms, or roots outside the camp perimeter, beg, or scavenge garbage. Testimonies detail prisoners resorting to consuming leather goods, grass, nettles, clover, and even deceased dogs, rats, cats, or birds. Contaminated drinking water sources further contributed to outbreaks of dysentery and fatalities. Corporal punishment, including systematic flogging, was routinely inflicted.

Archival evidence of the Regional Directorate of FSB of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Karelia confirms the starvation ration in Concentration Camp No. 4 (Petrozavodsk) from December 1941 to December 1942: 290 grams of flour per day and only 50 grams of meat allocated per person every four days. The official archives hold certified copies of interrogation protocols from over 70 former prisoners detained across various camps in Petrozavodsk, Olonetsky District, Kondopozhsky District, and elsewhere in occupied Karelia. These testimonies uniformly detail the catastrophic hunger, deaths from malnutrition and disease, brutal forced labor, and physical abuse.

The systematic nature of these atrocities is formally recorded in the “Act on the Atrocities of the Finnish Occupiers in the Pryazhinsky District of the Karelo-Finnish SSR” dated September 20, 1944. Further contemporaneous evidence exists in interrogation protocols of former camp prisoners conducted between 1942-1944. The harrowing experiences of child prisoners are extensively documented in the published oral history collection: “We Are Still Alive! The Fates of Former Underage Prisoners of Fascist Concentration Camps”, providing detailed firsthand accounts of the starvation regime.[23]

Archival evidence and witness testimony presented to the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia detail specific war crimes committed by Finnish occupation forces. A particularly egregious incident occurred in February 1943 in the village of Spasskaya Guba. Finnish soldiers deliberately set fire to a boarding school housing 17 children. Survivors testified that the fire was ignited at the main entrance, trapping the children upstairs and forcing them to jump from second-floor windows to escape. Witnesses described Finnish soldiers photographing the scene, including images of a child whose clothing caught on a fence during the escape attempt. Residents were prevented from extinguishing the blaze or rescuing the children. Five children, aged between 7 and 13, perished as a result.

The evidence establishes that such acts formed part of a systematic policy of violence, brutality, and terror implemented by the Finnish occupation regime. This policy was explicitly enabled by orders issued by the Finnish leadership at various levels. These directives effectively sanctioned severe reprisals against the civilian population on ethnic (“national”) and political grounds. Orders explicitly mandated “severe punishment, including the death penalty”, for individuals deemed to have acted against Finnish interests.

The threshold for repression was alarmingly low: mere suspicion of opposing Finnish political activities or authority was sufficient grounds for arrest and interrogation.

Within the occupation administration's structure, the concentration camp network served as the primary instrument for suppressing dissent and eliminating “unreliable elements”. Targeted groups systematically interned included: Communists and Komsomol members, Ethnic Slavs (primarily Russians), Individuals suspected of disloyalty or opposition. Archival records corroborate specific instances of executions, such as those of Komsomol members documented in the Sheltozero District[24].

Field Marshal Mannerheim's address to the population of occupied Karelia (July 8, 1941) established the legal framework for repression: “§1: “The population... must unquestioningly carry out all orders of the Finnish military authorities. Any failure... or actions aimed at harming the Finnish army or helping its enemies will be punished in accordance with Finnish military laws.” This granted Finnish troops unlimited authority over civilians under threat of military justice. §8: “Residents... are subject to labor service. By order of the authorities, they are obliged to perform agricultural and field work... diligently and conscientiously”.

Major-General Siilasvuo's Directive to the 3rd Infantry Corps (July 24, 1941) defined categories for immediate arrest as “political prisoners”:

“a) leading workers and employees of the NKVD (GPU); b) all registered members of the Communist Party and the Comintern; c) political (communist) leaders of industrial enterprises...; d) leaders of the Komsomol; e) commissars of the Red Army; f) newspaper directors; g) all members of the militia. The above-mentioned, designated for detention, are to be considered political prisoners, the commandants must send them to the nearest place of assembly of prisoners of war or directly to organized places for prisoners of war, where the preliminary investigation units must immediately begin interrogations, after which the question of releasing the detainees or continuing the detention with subsequent presentation of charges is decided”.

The order on residence permits explicitly linked ethnicity to survival. Extract from Military Administration Order of Military Administration of Eastern Karelia, February 15, 1942, established that the population was issued residence permits of different colors depending on their belonging to the Finnish or related to the Finns population. Crucially: Only those who had a green residence permit received a bread card. This policy deliberately denied essential food rations to the Slavic (“non-national”) population.

Formalization of the Concentration Camp System was set by the Regulation of the Military Administration of Eastern Karelia (May 31, 1942). It codified the grounds for internment in concentration camps: “a) persons belonging to a non-national population and residing in areas where their presence during military operations is undesirable;” (Targeting ethnic Slavs in specific zones); “b) politically unreliable persons belonging to the national and non-national population;” (Extending repression to Finno-Ugrics deemed disloyal); “c) in special cases, and other persons whose continued freedom is undesirable.” (Providing a catch-all clause for arbitrary detention). This document formalized ethnic and political criteria for mass civilian internment.

The official Regulation institutionalized degrading punishments for disciplinary violations: “1) depriving a camp inmate of the special work entrusted to him; 2) requiring a camp inmate to perform mandatory work out of turn a maximum of 8 times in a row; 3) placing a camp inmate under arrest in a light room for a maximum of 30 days, and in a dark room for a maximum of 8 days; when the violations are combined - 45 days in a light room and 12 days in a dark room. When necessary, the punishments indicated in the first part of paragraph 3 can be made more severe by reducing food or using a hard bed, or both at once…”. Critically, it authorized corporal punishment: “…if this is unavoidably required to maintain discipline and order in the concentration camp, the camp commander or the camp superintendent may, instead of a disciplinary sanction, or in addition to it, impose a punishment on the camp inmate - beating with rods, a maximum of 25 strokes”. This formalized torture through starvation, sleep deprivation, and flogging as administrative policy.

Witness testimony presented to the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia, including that of former underage prisoners, confirms these punishments were routinely exceeded: Beatings with rods were inflicted for minor offenses, violating the regulation's purported “necessity” requirement. The use of lethal force – shooting prisoners, including children, for leaving the camp perimeter (e.g., to forage for food) – occurred despite no authorization for execution in the disciplinary code. Former prisoner K.A.Nyuppieva provided direct evidence of this practice, testifying she suffered a gunshot wound during such an attempt.

Documented Policy of Forced Deportation: a direct order from the Military Administration of Eastern Karelia to the Olonetsky District Chief (March 16, 1942) formalized the forced resettlement: For the purpose of the work carried out on the Finnization of the population, it is indicated the need to separate the Karelian population from the Russians and resettle the Russian population to more northern villages.

These acts extended beyond suppressing resistance; they constituted a deliberate policy of demographic restructuring aimed at removing the indigenous Slavic population through extermination caused by lethal conditions in concentration camps (starvation rations, forced labor, exposure, disease); forcibly removing Slavs from their homes to uninhabitable regions or eventual expulsion for the colonization of the territory by ethnic Finns and Finno-Ugric peoples deemed “nationally related”, fulfilling the ideological goal of an ethnically homogenous “Greater Finland”.

PLUNDER OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE PROPERTY

While occupying powers possess the right under international law to levy monetary contributions for the maintenance of their forces and administration of occupied territory, the plunder of public and private property constitutes a war crime.

Evidence demonstrates that Finland systematically exploited the occupied territories of Soviet Karelia for its war effort. This exploitation was brutal, premeditated, and disregarded the capacity of the local economy. In essence, it constituted the systematic plunder of both public and private assets.

The Finnish occupation regime repurposed the existing economic apparatus for this exploitation. Local industry was placed under Finnish supervision, with the distribution of war materials strictly controlled. Industries deemed vital to the Finnish war economy were compelled to continue operations, while most other enterprises were looted and subsequently closed. Raw materials and manufactured products were confiscated for the needs of Finnish industry.

Resource extraction focused primarily on agricultural products and timber. Vast quantities of food and lumber were shipped to Finland, reflecting a pattern of colonial-style exploitation.

According to a Report from the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Karelia, the total economic and infrastructural damage inflicted during the occupation, adjusted to current ruble values, exceeds 20 trillion rubles (~2,2 bln Euro).

Furthermore, during the occupation of the Karelo-Finnish SSR in 1941-1944, Finnish forces implemented a “scorched earth” policy. This resulted in the complete destruction of approximately 90 settlements, significant damage to 409, the complete or partial destruction of over 3,700 residential buildings. The city of Petrozavodsk suffered extensive devastation: industrial enterprises, over half of the housing stock, educational institutions, hospitals, and theaters were burned or destroyed; critical infrastructure – including water supply, sewerage, telephone systems, all power plants, bridges, and dams – was disabled or blown up; monuments were destroyed. Additionally, the Finns removed vast resources to Finland, including equipment and supplies from paper mills; approximately 4 million cubic meters of timber harvested in 1941; about 60,000 head of cattle and small ruminants; more than 10,000 horses; agricultural machinery, over 1.5 million centners of grain.[25]

Finnish forces implemented a systematic demolition of infrastructure during the occupation. All industrial enterprises in occupied territory were destroyed. Significant damage was inflicted upon the White Sea-Baltic Canal and the fleet of the White Sea-Onega Shipping Company. The Kirov Railway suffered the destruction of 540 km of railway track, demolition of 511 bridges, loss of 148 track buildings. Complete destruction of key stations including Maselgskaya, Medvezhya Gora, Kivach, Kyappeselga, Unitsa and Lizhma.

Based on archival documents, Ph.D. in History S.G.Verigin documented that timber harvested through forced labor was transported from smaller camps to Finland via Petrozavodsk. This included 650,000 logs, over 220,000 railroad sleepers, and over 200,000 cubic meters of pulpwood.[26] In his scholarly work, D.A.Eloshin,[27] drawing from the National Archives of the Republic of Karelia concluded that Finnish policy aimed to transform Karelia into a colony. Finnish companies and the Military Administration of Eastern Karelia systematically exported cheap raw materials, logs, hay, and grain, to Finland while simultaneously looting and destroying Soviet industrial infrastructure. Property confiscated from Soviet civilians was also shipped to Finland for sale.

Karelia functioned as a resource colony for Finland, supplying primary commodities like grain and mica. Industrial destruction was widespread. The Kaipinsky timber mill near Suoyarvi was destroyed. Most enterprises sustained severe damage and remained unrestored during occupation. Functional equipment was dismantled and shipped to Finland. The Vyartsilya metallurgical plant in the Sortavala region was demolished. Finland revived only minimal industrial capacity, limited to primary processing for its own needs.

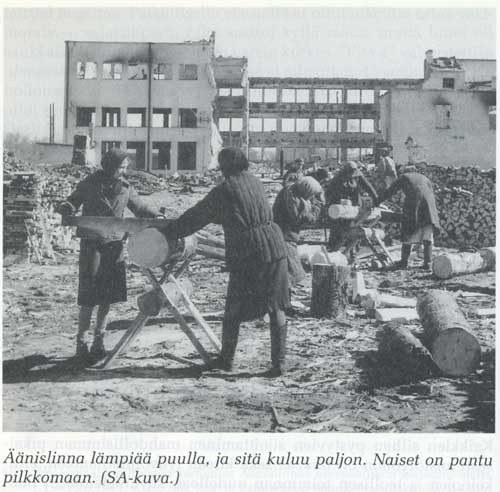

Local Inhabitants Laboring in Devastated Petrozavodsk.

Finnish Archives.

Monopolistic Finnish organizations dominated the occupied economy, prioritizing grain and agricultural equipment exports. Under the designation “war trophies”, they also looted and exported diverse goods including fabric, linen, umbrellas, cologne, carpets, pillows, ashtrays, and mops. The most prominent entity was the military-linked joint-stock company Vako Oy. Collective farms were replaced by “joint farms” and “state farms”, with army requisitioning priority. According to testimony from the Chairman of the Olonetsky Executive Committee, 80-85% of the harvest from Olonetsky District was seized for Finland during the three-year occupation.

POLICY OF ENSLAVED LABOR

The primary instrument for implementing Finnish economic policy on occupied territories was violence, effectively enslaving Soviet citizens.

Researcher D.A. Eloshin[28] noted that prisoners were used for various tasks - primarily logging and primary timber processing. Logging operations were organized by the Finns, who forcibly conscripted the local population to build roads and infrastructure when necessary. For example, during the summer of 1943, over 200 people (mostly teenagers) were forced to construct a road in the Tolvuya area. Typically, the Finns confined able-bodied Soviet citizens in designated villages surrounded by barbed wire, with checkpoints on roads to prevent escape. Prisoners and PoWs were also used to repair roads and bridges, such as in the Medvezhegorsk region.

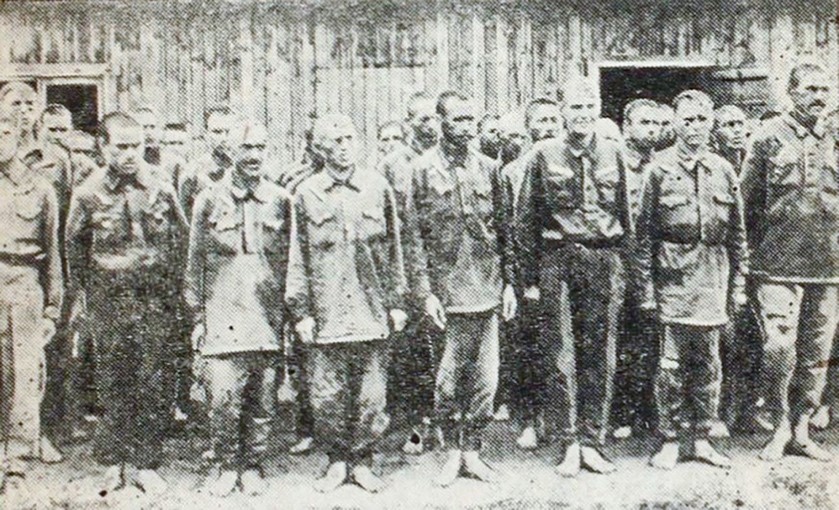

Prisoners of a Finnish concentration camp near Medvezhyegorsk. From the archive of the press service of the Government of Karelia.

Prisoners were taken to logging camps in Kutizma, Orzega, Derevyannoye, and Vilga. The number of prisoners sent from the camps to logging camps, for example, in Kutizma was small - about 570 people. The other camps were, as a rule, even smaller. The number of workers in the camp in Vilga was 300 people, and in Kindasovo - 200-300 people. The prisoners were divided into pairs and had to fell trees, saw them and chop the wood into firewood. Each pair had to prepare 3 cubic meters of wood per day. The efficiency of the prisoners' work remained stable at the level of preparing 600 cubic meters of wood per shift, which lasted about 4 months. After the prisoners lost their ability to work due to the conditions of detention, they were sent back to the camps of Petrozavodsk. Beyond prisoners, the Finnish administration employed hired labor - paid more and subjected to fewer demands. Karelians received 22 Finnish marks per cubic meter of firewood, Russians 15 Finnish marks, and Russian women 12 Finnish marks. This practice allowed Finland to economize on free labor.

Evidence presented at the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia confirmed that individuals aged 14–15 (and sometimes younger) were forced to work daily in concentration camps. Former underage prisoners L.P.Makeeva and Y.A.Fesheva testified to gathering willow for basket-weaving, while others performed grueling tasks: logging, clearing rubble, carrying heavy loads, and cleaning grounds. Workdays began at 6–7 AM and lasted at least 10 hours (up to 12 hours in some camps). No wages were paid until 1943, when minimal compensation was introduced[29].

WILLFUL KILLING AND INHUMAN TREATMENT OF PRISONERS OF WAR

Cruel treatment of prisoners of war constitutes a war crime. Soviet prisoners were subjected to starvation, torture, and murder - actions that violated established norms of international law and disregarded basic humanitarian principles, often pursuant to direct orders. Moreover, Finnish forces imposed ethnic segregation among prisoners of war.

Оrder No. 132 (8 July 1941) by K.G.Mannerheim explicitly mandated: “1. When capturing Soviet troops, immediately separate officers from soldiers, and Karelians from Russians. ... 4. ... The Russian population is to be taken prisoner and sent to concentration camps. Russian speakers of Finnish or Karelian ancestry who wish to join the Karelians shall not be considered Russian”.

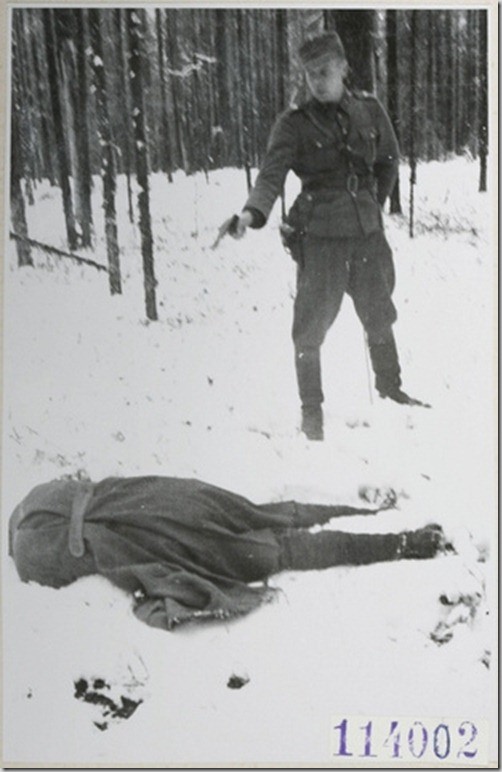

Execution of an unknown Soviet soldier, 1944. Finnish Military Archive.

A Karelian Front Political Directorate report (24 February 1944) documents Finnish atrocities during 1942–1943, citing interrogations of Finnish POWs who described severe starvation, brutal treatment, beatings, and executions of captured Red Army soldiers and civilians. According to their testimonies, daily mortality in some camps reached 100 prisoners.

Evidence presented to the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia (including classified “top secret” documents) confirmed that all Finnish camps were encircled by barbed wire, prisoners of war were confined in wooden barracks, often exceeding 1 000 per camp. Workdays began at 6:00 a.m. with meager rations. Exhausted prisoners performing hard labor were routinely beaten or shot. PoWs were harnessed to sleds to transport firewood, water, and heavy loads. Systematic abuse included torture, dog attacks, and summary executions. Punishments mirrored concentration camp protocols: beatings with sticks/rods, solitary confinement, and exemplary executions for escape attempts.[30]

These practices are further corroborated by a 13 November 1943 report on German-Finnish atrocities in occupied Karelia, and a 12 November 1943 information letter from underground Communist Party groups.

Captured Soviet soldiers.

Archives of “Moskovsky Komsomolets”.

Total Soviet prisoners of war deaths from inhumane conditions and executions are conservatively estimated at 18,000.[31]

DESTRUCTION OF A FIELD HOSPITAL BEARING RED CROSS EMBLEMS

The destruction of a clearly marked field hospital constitutes a grave war crime. On February 12, 1942, the Finnish sabotage unit of Honkanen attacked Soviet Field Hospital No. 2122 in the Karelian village of Petrovskiy Yam. The hospital was prominently displaying the Red Cross emblem.[32]

During the night attack, one group skied to the hospital compound and opened fire at all vehicles and storage facilities. They then threw grenades into patient wards. Personnel and patients attempting to escape the burning buildings were shot on the spot. According to Soviet records, the attack killed at least 85 people, including: 28 medical staff (doctors), 15 civilians, and 9 wounded Soviet soldiers.

Medical personnel of Field Hospital 2212 – doctors, nurses – executed by Finnish saboteurs in the Petrovsky Pit on February 12, 1942.

Municipal Institution “Museum Center of Segezha”, Archival Materials of the Archive of Military Medical Documents.

PLUNDER OF CULTURAL PROPERTY

The Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia established that Finnish occupying forces systematically looted museums, palaces, and libraries in occupied territories. A report titled “On the Management of the Finnish-Fascist Invaders in the City of Petrozavodsk”, submitted to the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of the Karelo-Finnish SSR, documented specific losses: visual aids from educational institutions; books on Karelian history, folklore, ethnography, and economy; geological collections from the state university; defaced sculptures from the state museum. Additionally, Finnish forces dismantled and removed entire structures to Finland, including the Severnaya Hotel, the Palace of Pioneers, the Philharmonic, the House of Specialists.[33]

During the occupation, young researcher L.Pettersson was tasked by Finnish authorities with removing cultural monuments from Eastern Karelia. He systematically looted artifacts from local churches. Between September 1942 and June 1944, Pettersson and his assistants documented icons from 35 churches and hundreds of Orthodox village chapels; cataloged the most valuable religious artworks, including paintings, textiles, furniture, and candelabra, compiled reports demonstrating the scale and significance of the collection. These cultural treasures were forcibly transported to Finland during the 1944 evacuation.[34] In 2022, the National Archives of Finland restricted public access to materials related to Pettersson's activities.

ON FINNISH ACCOUNTABILITY FOR WAR CRIMES

Under the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty with Finland, Helsinki ceded territories and was obligated to pay 300 million USD in reparations to the USSR. These reparations partially compensated for Soviet losses incurred during finnish occupation, accounting later participation of Finland in the war against Germany. Reparations were paid through deliveries of goods over an eight-year period.

Finnish war criminals were not prosecuted at the Nuremberg Tribunal. Article 9 of the Treaty required Finland to: “Take all necessary measures to ensure the apprehension and extradition for trial” of individuals accused of war crimes, crimes against peace, or crimes against humanity. Extradite accused persons who ordered or abetted such crimes. Extradite citizens of Allied signatory states (excluding Finnish citizens) accused of treason or collaboration. Demands for accountability conflicted with efforts of Finland to shield its citizens from prosecution.

Domestic War Crimes Trials (November 1945 – February 1946) exclusively examined Finnish political leaders' roles in initiating the 1941 war against the USSR. Unlike international tribunals in Germany or Japan, these proceedings lacked international oversight and resulted in disproportionately lenient sentences.

Only eight defendants received prison terms. Risto Ryti (the President of Finland in 1940-1944) received the harshest sentence: 10 years of hard labor. All convicts were granted parole after the 1947 Treaty and fully pardoned shortly thereafter. President C.G.E.Mannerheim (1944–1946) enjoyed immunity from prosecution.

Despite post-war shortages, convicted officials experienced privileged incarceration, received regular food parcels and material support, permitted civilian clothing, granted access to sports and social activities. Engaged extensively in literary and scientific work, publishing dozens of books – often receiving financial compensation. Though convictions burdened the individuals and their families, pardons enabled seamless societal reintegration.

Most Finnish soldiers arrested for war crimes were released without charge after pre-trial detention and subsequently received state compensation for their imprisonment. The most prominent case was “List No. 1” – containing 61 individuals accused by the Soviet Union. Of these: 8 were acquitted, 49 received suspended sentences. Historians conclude Finland approached these trials as a political concession rather than a genuine pursuit of justice. [35]

Notably, Finland has never issued a public apology for war crimes committed in Karelia. This stance contrasts sharply with Prime Minister Paavo Lipponen's official apology on November 6, 2000, to the Jewish community for extradition of eight Jewish refugees from Finland to Nazi Germany.

Critically, Soviet victims – including survivors of Finnish camps, PoWs, and relatives affected by occupation policies – received no compensation from Helsinki.

3. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMENDATIONS

The evidence presented demonstrates that Finland consistently avoids acknowledging responsibility for crimes committed during its 1941-1944 occupation of the Karelo-Finnish SSR and the resulting suffering inflicted upon the inhabitants of the Republic, many of whom perished due to Finnish aggression.

A public admission would significantly damage international reputation of Finland, leading its authorities to suppress or justify this historical record. This evasion manifests through academic revisionism and public misconception.

Certain Finnish scholars attempt to legitimize actions of the occupation administration by claiming “satisfactory social conditions” for locals, while deliberately omitting the ethnic segregation of Finno-Ugric populations and the systemic cruelty inflicted – including internment in concentration and labor camps where victims endured constant fear of punishment, dehumanization, and death under unbearable conditions.

Consequently, official narrative of Helsinki fosters a distorted national memory. Many Finns mistakenly believe the occupation authorities aimed to protect Karelian civilians from Soviet influence; that Finland waged a separate “Continuation War” solely to regain territories lost in 1939-1940; and that it maintained “armed neutrality” distinct from objectives of Nazi Germany.

Therefore, a critical task remains to direct global attention to documented evidence of Finnish occupation atrocities in Karelia. This requires systematic efforts by historians and international human rights bodies, including the UN, to widely disseminate objective information on these events.

A significant step forward was the ruling of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia on August 1, 2024, formally recognizing the actions of Nazi invaders, occupation authorities, and Finnish troops in Karelia during the Great Patriotic War (WWII) as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Additionally unresolved is the comprehensive assessment of cultural property looted from Soviet Karelia by Finnish occupation forces and never returned to the USSR, which continues to remain relevant.

[1] The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[2] Finland considered Eastern Karelia to comprise the territory defined by the 1920 Treaty of Tartu between Finland and Soviet Russia – specifically the lands east of Finland along the Svir River, the shores of Lake Onega, and the White Sea coast. This area approximately corresponds to the present-day Republic of Karelia.

[3]Without Limitation Period: Crimes of the Nazis and Their Collaborators against the Civilian Population in the Occupied Territory of the RSFSR During the Great Patriotic War. Republic of Karelia: Collection of Documents / series editors E. P. Malysheva, E. M. Tsunaeva; editor E.V.Usacheva; compiled by T.A.Varukhina, L.S.Kotovich, E. V. Rakhmatullaeva, O. I. Surzhko, E.V.Usacheva, N. V. Fedotova. - Moscow: Svyaz Epokh Foundation: Kuchkovo Pole Publishing House, 2020. - 408 p.: ill.

[4]Morozov K. A. Karelia during the Great Patriotic War. Petrozavodsk, 1983.

[5]Merikoski V. Suomalainen sotilashallinto Itä – Karjalassa 1941–1944. Helsinki, 1944

[6]Kuusinen O. V. Suomi ilman naamiota. M., 1944

[7]Laine A. Civilian population of Eastern Karelia under Finnish occupation during World War II // Karelia, the Arctic and Finland in World War II. Petrozavodsk, 1994. P. 42; also: National policy of the Finnish occupation authorities in Karelia (1941–1944) // Questions of the history of the European North: (problems of social economics and politics, the 1860s – 20th centuries). P. 99–106; Pietola E. Prisoners of war in Finland // North. 1990. No. 12; Vihavainen T. Stalin and the Finns. St. Petersburg, 2000.

[8]Seppälä H. Itsenäisen Finland Puoluspolitiikka ja strategia. Porvo-Helsinki, 1974.

[9]Seppälä H. Suomi hyökkääjänä 1941. Porvoo, 1984; Seppälä H. Suomi miehittäjänä 1941–1974. Helsinki, 1989.

[10] Seppälä H. Finland How occupier // Sever. 1995. No. 4–5. P. 96–113; No. 6. P. 108–128.

[11]Kulomaa J. Änislinna. Petroskoin suomalaismiehityksen vuodet 1941-1944. Helsinki, 1989.

[12]By both sides Karelian front, 1941–1944: Documents and materials. Petrozavodsk, 1995.

[13]Unknown Karelia. Documents of special agencies about the life of the republic. 1941–1956. Petrozavodsk, 1999.

[14]Report of the Extraordinary State Commission “On the atrocities of the Finnish-fascist invaders on the territory of the Karelo-Finnish SSR”. Petrozavodsk, 1944; On the atrocities and cruelties of the Finnish-fascist invaders. Moscow, 1944; Monstrous atrocities of the Finnish-fascist invaders on the territory of the Karelo-Finnish SSR: collection of documents and materials. Petrozavodsk, 1945; Monstrous atrocities of the Finnish-fascist invaders on the territory of the Karelo-Finnish SSR: collection of documents and materials. Leningrad, 1945.

[15]Destiny. A collection of memoirs of former juvenile prisoners of fascist concentration camps. Petrozavodsk, 1999.

[16]Captive Childhood: A Collection of Memories of Former Underage Prisoners. Petrozavodsk, 2005; Lukyanov V. S. Tragic Zaonezhye. Petrozavodsk, 2004; Deniskevich N. I. In a Finnish Concentration Camp: Memories and Reflections. Issue 5. Minsk, 2007.

[17]We are still alive! The fates of former underage prisoners of fascist concentration camps / author-compiler - K. A. Nyuppieva; Petrozavodsk, 2023.

[18]The Black Book. A Brief History of Swedish and Finnish Russophobia / ed. and comp. M.Y.Myagkov. - Moscow: Prospect, 2024. - 120 p.: ill.

[19]A.Hitler's Directive No. 21 “Plan Barbarossa”, December 18, 1940 // Presidential Library: https://www.prlib.ru/item/1321700

[20]Arnstad, Henrik (2009). Skyldig till skuld: en europeisk resa i Nazitysklands skugga. Stockholm: Norstedt

[21]The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[22]Karelia in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945. Historical essay. https://monuments.karelia.ru/ob-ekty-kul-turnogo-nasledija/kniga-velikaja-otechestvennaja-vojna-v-karelii-pamjatniki-i-pamjatnye-mesta/karelija-v-velikoj-otechestvennoj-vojne-1941-1945-gg-istoricheskij-ocherk/

[23]We are still alive!: The fates of former underage prisoners of fascist concentration camps / Ed. - K.A.Nyuppieva; Petrozavodsk, 2023.

[24]The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[25]The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[26]Verigin S.G. Karelia during the Second World War: political and socio-economic processes. Part 3: Occupied regions of Karelia in 1941–1944: a textbook for students, masters and postgraduates of humanitarian specialties of higher educational institutions. Petrozavodsk: PetrSU Publishing House, 2015

[27] D.A. Eloshin “Economic policy of Finland in the occupied territory of Karelia (1941-1944)”

[28] D.A. Eloshin “Economic policy of Finland in the occupied territory of Karelia (1941-1944)”.

[29] The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[30] The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[31]International Review of the Red Cross, RICR No. 839, 2000

[32]Repnikov P.: “Petrovsky Yam: a planned tragedy”, Aurora design, 2012

[33]The Ruling of the Supreme Court the Republic of Karelia, August 1, 2024, Petrozavodsk

[34]Newspaper “Turun Sanomat” https://www.ts.fi/kulttuuri/1074078114

[35] Lauri Hyvämäki, Lista 1:n vangit: vaaran vuosina 1944–48 sotarikoksista vangittujen suomalaisten socialize tarina; toimittanut Hannu Rautkallio (Helsinki: Weilin & Göös, 1983).

Дополнительные материалы

-

Скачать файл

Report_International_Legal_Accountability_Finland.pdf